Each collection that Là Fuori makes has a secret hidden in its history.

A small wonder that is revealed towards the end of each story.

Almost by magic, almost by nostalgia, our exploratory heart does not resist and becomes an echo of a tradition.

The secret of today’s story is the Indigo of Vietnam, through the habits and customs of the Hmong ethnic group, of which our artisans belong.

Indigo dye is an ecological, sustainable and fair trade income for many ethnic groups on the Sapa plateau.

Could it also be for us?

The Indigo’s route between tradition and sustainability

NATURAL DYEING TECHNIQUES IN VIETNAM

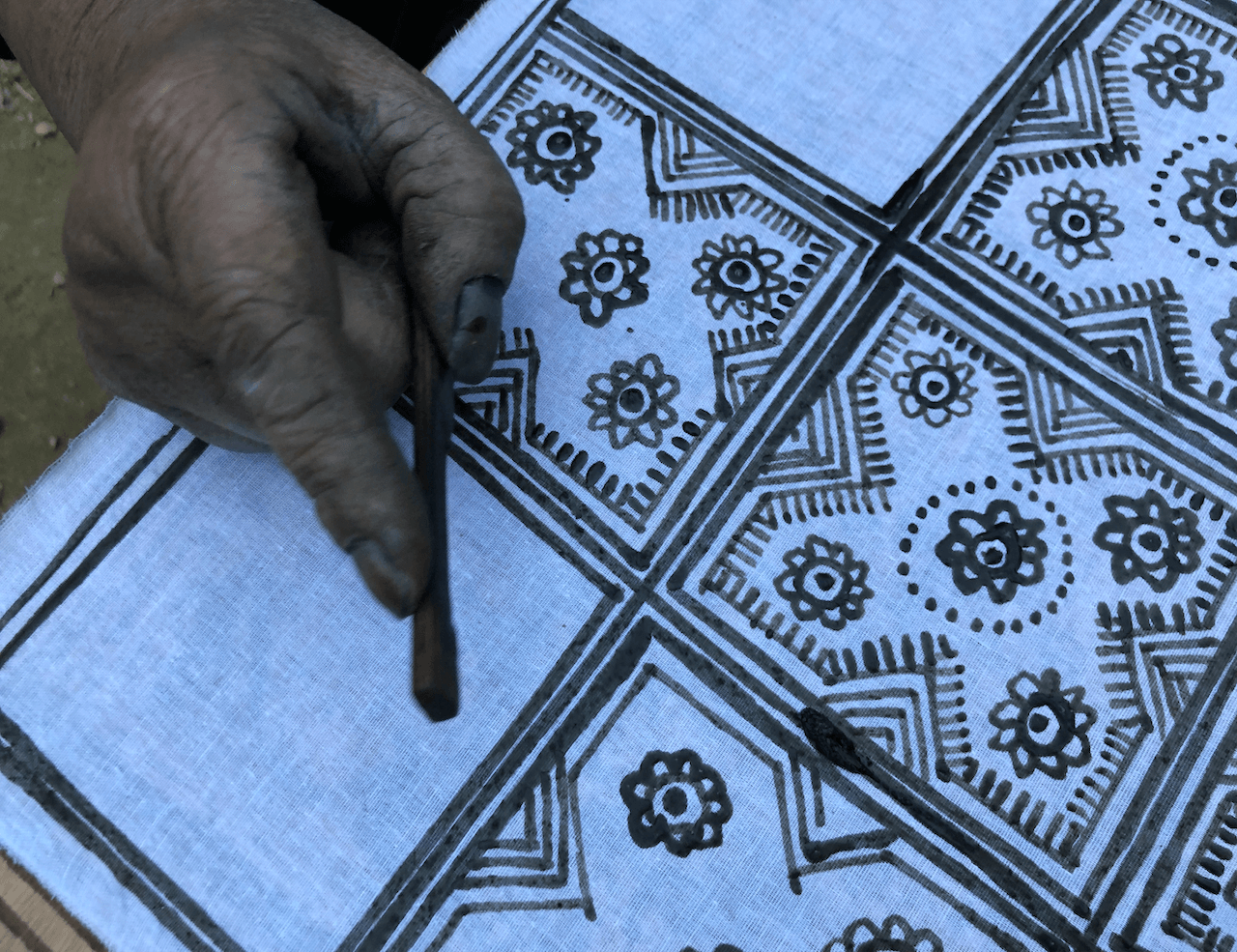

Hmong women push bands of fabric into vats of bubbling blue dye. Thirty minutes later, the hands are tinged with indigo, turquoise, and or purple; they fish out the cloth and spread it out to dry. The longer the fabric is in the dye, the darker it will become. Eventually, the fabric will oxidize to a distinctive deep blue, the recognizable cobalt of blue jeans.

As the fabric dries outside their thatched homes, the women continue daily activities from childcare to farming to collecting firewood – their hands are often deeply scarred from decades of labor. Repetition of dyeing the fabric indigo over the years has stained their fingers as bright as bluebirds.

INDIGO LIKE THE TEARS OF THE GODS

It is not uncommon to find magical blue pools in the homes of the artisans who work with us.

An old lady told me they are the happy tears of the gods.

This happiness that becomes color for human beings made our stay in one of these humble abodes indelible.

Traditional Hmong clothing is dyed an indigo blue so dark it becomes black. The method – dyeing, spreading and drying – must be repeated twice a day for a month to get the right color depth. Depending on the Hmong subgroup – Black, Flower, Striped or Red – the fabric could be embroidered with a variety of bright patterns. Menswear is typically left sober and simple.

For some tribes, the deeper the indigo, the more precious the fabric becomes. Some say they can tell when a thread of fabric is finished only by the color of a craftsman’s hands.

INDIGO LEAVES AND HEMP HARVEST

High in the hills above Sapa, tribes continue to dye Indigofera plants that are native to Vietnam.

The plants with their broad green leaves and slightly purple flowers are scattered on the slopes near the homes of the Hmong. They typically produce a crop twice a year.

The leaves of the Indigofera plant are harvested and fermented with various additives such as rice wine, urine or lye.

When the fermentation process is complete (times that Hmong women seem to know instinctively), the leaves are extracted. They are then left to oxidize in the open air. The dried leaves can be ground into powder or paste and stored until ready to use the mixture on the fabric.

The fabric itself is traditionally spun from hemp plants.

INDIGO, ON THE SPICES ROUTE

Indigo dye has an ancient history. Its exact origins aren’t clear, but the name and mass appeal likely came from India. Eventually, the spice and slave trade introduced indigo to the world. Indigo blue became a color associated with luxury during the colonial era. Its growing demand spawned the implementation of indigo farms all the way to the Americas in the 1600s. This production was eventually used to dye denim and indigo became the iconic shade of American blue jeans in the early 20th century.

The humid climate in Southeast Asia makes it difficult to trace the history of indigo in Vietnam. Ancient textile samples have been lost or disintegrated. However, some historians believe that techniques for turning Indigofera plants into dye were independently discovered by numerous cultures in Asia in the same period before the medieval period.

TRADITION OR SUSTAINABILITY OR BOTH ?

In addition to the Hmong, other ethnic groups in Vietnam, such as the Dao, Nung, and La Chi, maintain strong indigo dyeing traditions. Some even sell their fabrics to markets for the income of their communities. But now, millions of pounds of synthetic indigo dye are produced every year just to color blue jeans. As a result, the traditions of natural dyeing are quickly pushed aside in favor of modern methods.

Out there she wondered: “Why should buyers prefer natural indigo dye to synthetic?”

Sustainability is a word that has been used (perhaps overused) a lot over the past five years. Sometimes, it is added to a product description simply to target customers looking to be more conscientious about their carbon footprint. There is also a word for this practice of false environmentalism: “greenwashing”.

However, when it comes to companies that “bluewash” falsely claiming to use natural indigo dyes, they risk more than just bad publicity. In this case, sustainability is synonymous with preserving the environment and heritage of ethnic communities.

When natural indigo dye is made, it is possible to make fertilizer from the leaves after the color has been extracted. The water can then be used to irrigate the crops. On the other hand, synthetic indigo is composed of petrochemicals and formaldehyde, which leave chemical waste that pollutes the water.

In some ethnic villages, the techniques of how to collect and prepare natural indigo are not passed down to younger generations. Sometimes, declining knowledge is kept in the minds and hands of older women in communities. Many of them are over 80 years old. Buying authentic, hand-made fabrics can give lasting employment to Vietnam’s ethnic groups.

The Stories of Sapa collection does not only want to celebrate Vietnamese stylistic lines but loves to challenge itself between the aforementioned tradition and sustainability. Dress well, be inspired but above all preserve the manufacturing techniques of the Hmong ethnic group. The beauty of their heritage raises their hands. The beauty of their heritage on represented on our clothes.